By Dan W. Osborne -

Most of us have felt the increasing frustration experienced when trying to have a constructive conversation that seems to just go nowhere.

This experience is at the very heart of why we see increasing polarization and division in society. It’s also one reason why so many people are experiencing stress in dealing with close relationships where each holds significant differences of opinion regarding important issues.

So let’s look at some of the problems – and possible solutions – that are behind our inability to have productive disagreements.

One of the biggest problems is “identity politics”. It’s the term used to describe someone who allows their own sense of self to be inextricably tied to their beliefs. This often results in them having little interest in learning why their beliefs might be untrue or in changing their perspective. In other words, it can make one narrow or closed minded.

Paul Graham’s theory ( http://www.paulgraham.com/identity.html ) states that while its true that politics and religion are the topics we most associate with difficult conversations with closed minded people, it can be any topic where people don’t feel they need to have any particular expertise to have opinions about it. All they need is strongly held beliefs, and anyone can have those.

Graham goes on to say: “Which topics engage people’s identity depends on the people, not the topic. For example, a discussion about a battle that included citizens of one or more of the countries involved would probably degenerate into a political argument. But a discussion today about a battle that took place in the Bronze Age probably wouldn’t. No one would know what side to be on. So it’s not politics that’s the source of the trouble, but identity. When people say a discussion has degenerated into a religious war, what they really mean is that it has started to be driven mostly by people’s identities.” Since people can’t think clearly about anything that has become part of their identity, it would make sense to let as few things into our own identity as possible so that we can remain open minded during constructive conversations.

Constructive conversations broadly fall into three types, ones that: (1) seek truth and understanding (2) are designed to persuade another person (3) seek to gain power over another person. Another problem, discussed by Julia Dhar, ( Julia Dhar: How to have constructive conversations | TED ) occurs when you’re conversing with someone who is only interested in using the conversation to persuade or gain power because it makes any form of agreement or ability to find common ground unlikely.

That’s why it’s important to establish beforehand with all parties the purpose of the conversation. One way is to speak in broad terms of what all parties would like to see in the future regarding the issues in question. This prevents details and specifics becoming obstacles early in the process. For example, if you were engaged in a conversation about zoning you might ask: “how would you like to see this neighbourhood look 5 years from now?”

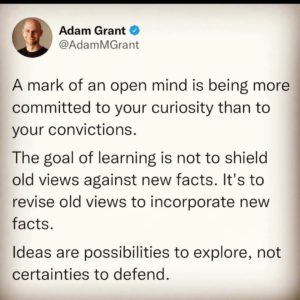

Once the purpose of the conversation is established, each side should commit to being genuinely open to persuasion by committing to the possibility that they could be wrong. The “humility of uncertainty” can help people keep an open mind and feel less identified with their views.

Another way to overcome the problem of a closed mind is to express genuine curiosity regarding the other person’s perspective. As Julia says, it’s as simple as saying: “I never thought about it that way before, what can you share that will help me see what you see?” One of the productive effects of this phrase is that it often results in the other person wanting to learn more about your views in response to your curiosity about theirs.

All these solutions can help move the dialogue forward in your discussion which should be your primary objective. You should avoid “going for the win” by trying to completely convert all parties to your point of view at your first meeting. Instead, think about the conversation as a kind of a stepping stone where common ground can be identified and applied in finding an agreement that may take several discussions.

Each of these subsequent conversations can help you further sharpen your own logic and insights thereby improving your arguments and making them more understandable to others.

Constructive conversations can be challenging but by understanding the associated problems and some potential solutions we can find common ground and make our discussions much less stressful.